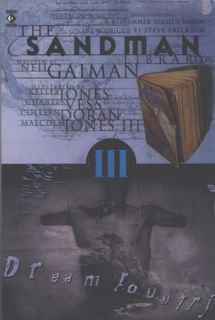

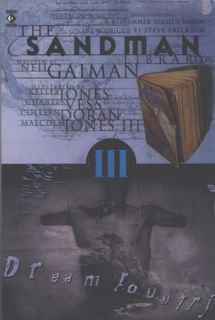

The Sandman: Dream Country (#17 -#20)Anna said she wished she was fourteen

The Sandman: Dream Country (#17 -#20)Anna said she wished she was fourteen

I said I wished I was ShakespeareGerard Langley

Neil Gaiman's Sandman is a strange beast - a set of tales set in the world of dreams, the eponymous (anti?) hero being the lord of dreams, Morpheus. Morpheus often isn't the centre of attention, which is left to a parade of characters who range from mildly unhinged to grotesque and on to murderous. At its worst it drags into the gutter mind of psychopathic killers and B movie horror stunts, but Gaiman's Sandman doesn't do "bad" in any significant way.

This book is a collection of four separate tales which allowed a breathing space between the sublime madness of

The Doll's House and

Season of Mists, which I haven't read yet. In it we see a Gaiman stretching his literary muscles, and showing off his influences (something that might ordinarily be quite hidden) with a mastery which borders on boastful.

The first story,

Calliope, is to all intents and purposes a classical morality play. Richard Madoc is an author with writers' block. He visits an unpleasant older author, Erasmus Fry, and buys from him a captive nymph, Calliope. He takes the wretched Calliope home, imprisons her, rapes her, and immediately finds himself able to write. Calliope is now his

muse, a divine woman with the ability to inspire creativity. Madoc becomes rich and famous. Calliope, trapped now for sixty years, called on Oneiros, her name for the Sandman. Oneiros visits Madoc and asks him to free Calliope. When Madoc refuses, Oneiros overloads Madoc's brain by unleashing all his dreams. Driven to insanity, Madoc frees Calliope, and she in turn persuades Oneiros to end Madoc's madness. In the final scene, Madoc is left a shell, bereft of creativity.

The most shocking part of this is undoubtedly the rape of Calliope. Now rapes don't occur often in comic books, and when they do, they tend to make their mark, both within the story and in the outside world. This rape, though in no way gratuitous or sympathetic to the rapist, is low-key. The point of the story is Calliope's imprisonment, not her rape.

This is a story rich in classical references, and has all the hallmarks of stories found in Ovid's

Metamorphoses, a stitched together, tumbling stream of diverse folk tales which nevertheless holds together as one book. The rape of Calliope is best seen in this light: rape in Roman times did not, at least in stories, have the stigma it has now, and nymphs, particularly ones who went to wash in rivers, were often subjected to it. Calliope, incidentally, appears in

Metamorphoses, though only to recount another story.

Two classical elements which Gaiman stitches into this story are

kairos, the correct moment for an action to take place, and

hubris, excessive pride. When Oneiros visits Madoc, Madoc is presented with an opportunity to free Calliope and escape without punishment for his despicable actions. By refusing, he is showing his

hubris, his

kairos is past, and retribution is inevitable. It's possible Gaiman is unaware that this is the type of story which could have been written in antiquity, but I doubt it. Gaiman seems to put intent into everything.

The second story,

A dream of a thousand cats, could be, if you stripped out the grizzly bits with drowning kittens, almost a children's tale, reminiscent of the Brothers Grimm.

And then we're onto

A midsummer night's dream, whose title suggests that Gaiman is about to indulge in some hubris of his own.

You don't take on Shakespeare lightly. His language is archaic, his plots were a bit ropey and he has a enormous herd of Grade A Slappable thesbian fans, but you can't read Shakespeare without concluding he was one of the most gifted users of the language that English has ever known. In weaving a Shakespearean story into his own, Gaiman is almost inviting us to judge between him and Shakespeare, something no writer would be wise to do.

But Gaiman gets away with it, because he is knowledgeable, loves Shakespeare's work and is highly talented himself. He makes an excellent choice of play: by picking

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Shakespeare's dreamy comedy of libidinous Athenian druggies, rather than a more heavy-going tragedy like

Hamlet, Gaiman is making sure Shakespeare's characters won't look out of place, and also ensuring he can have some fun.

There's a healthy dollop of

recursion in this story, where there are multiple layers of stories. So we have Gaiman writing a story about Shakespeare, who appears acting in a a play which partly consists of actors doing a play. A story within a story within a story, if you like. Characters from Shakespeare's play appear alongside Shakespeare. It's all a bit complicated, has buckets of Shakespeare quotes and it's a joy to read. It even has some quality humour.

Shakespeare's Robin Longfellow: Thou speak'sk aright. I am that merry wanderer of the night

Gaiman's Robin Longfellow: "I am that merry wanderer of the night"? I am that giggling-dangerous-totally-bloody-psychotic-menace-to-life-and-limb, more like it.

What's also striking is Gaiman's knowledge of Shakespeare's works, and of his times. Gaiman's Shakespeare has done a deal with the Sandman: in return for his gifts, he has agreed to write two plays for him.

A Midsummer Night's Dream is the first, and while Gaiman doesn't say which one is the second,

The Tempest is the obvious candidate. These two plays both mix freely the everyday and imaginary worlds and play with the idea that dreams are a form of reality, which is, of course, what Gaiman is doing. That

A Midsummer Night's Dream is an early Shakespeare work and

The Tempest is his last is a superb touch: Gaiman is explaining Shakespeare's career by making these two plays the bookends of Shakespeare's deal with the Sandman.

And I love seeing Shakespeare's actors like Richard Burbage and Will Kemp: being actors before cinema, their performances are entirely lost to us, yet they still maintain a certain fame. Include a reference or two to Christopher Marlowe's death, and you have in Gaiman a writer who has either thrown himself into his work or, more likely, creating something from a pre-existing love.

The question I can't answer is how this story would appear to someone who didn't know Shakespeare's play. Are the references too obscure? Well, anyway, it's a good excuse to get to know some Shakespeare, which is overwhelmingly a better thing than chasing down, say, the

Vision and Scarlet Witch limited series.

The final story,

Facade demonstrates in its murkiness how comic book continuity, even when well handled, still has a degrading effect on the quality of a book. In it, an immortal character called "Element Girl" obtains release from life. It's not a bad story, but I found it confusing and opaque until I'd read it a few times. Continuity, while indulging its existing readers, demands a degree of study and patience in its new ones. This story's theme of immortals finding life unbearable (like Salman Rushdie's

Grimus) also has, I believe, a classical provenance.

This final story also highlights one of Gaiman's few weaknesses. Too often, Morpheus is used as a plot device in order to resolve everything. Sometimes you feel like if you whistled up Morpheus early, you could have everything resolved in three pages.

So, all in all, we have four stories which demonstrate that you don't have to write a fifteen part mega-plot in order to create something quite special. Gaiman shows himself to be literate, clever and surprisingly affectionate towards his characters. Comics simply can't get much better than this.