The boy wondering

All Star Batman and Robin the Whatever #1 - 2

I love rock supergroups. Take a drug-injecting singer, passive-aggressive bassist, psychotic drummer and virtuoso guitarist, add a dab of "hey we can put the show on right here" spirit, and you've got yourself a gig. Maybe even a once-in-a-lifetime album. The moment of horror comes when you realise they sound shite - butchering old standards, revamping their greatest songs as slow waltzes and, worst of all, indulging in twelve minute long fretwanks. It dawns on us, that, despite their individual talents, you need chemistry as well.

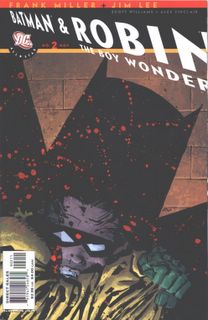

Which brings me to All Star Batman and Robin, produced by the comic creating supergroup of our times, Frank Miller and Jim Lee. While I'm not convinced the chemistry is exactly right, they have produced something genuinely thought provoking.

Miller, of course, wrote Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a jolly 1980s romp through a future dysfunctional Gotham populated by murderous street gangs, where civic society had broken down, though mercifully not enough for Gotham's gangster population to be deprived of the styling gel they need to keep their towering mohicans a-quiver. No matter who the artist, if you expect Miller to deliver something as good as that, you're probably in for a disappointment.

You can tell something's up from quite early on in issue #1, where we have several pages of a journalist romping round her apartment in her Agent Provocateur lingerie. This scene added nothing to the plot, and can only have been there because the creators wanted it. Perhaps Jim Lee likes painting semi-nude women? Most artists do.

And then there's the name. Does the phrase "Boy Wonder" have a cachet amongst regular Batman readers? In the world outside, phrases like that have been an embarrassment which comic books should want to shrug off, not plaster on the front of the world's best-selling comic book.

Self-indulgence is always a problem for famous creators. At the start of your career, your visions get blunted by spoilsport editors (some of whom, it has to be said, have the souls of 1950s Czechoslovakian Ministry of Supply bureaucrats), and once you get to the top of the tree, you're determined not to answer to those petty minded fools. Trouble is, editing is a very different skill to writing, and it improves most works. Do away with an editor, and writers are firmly on the path to JK Rowling bloat. You wonder, at times, if this could have been improved with a firmer editor at the helm.

I don't know much about Batman, and Robin not at all, so I'm a rarity in wanting to learn more about these characters. But you sense, with the strange comments and in-jokes which I can only guess may amuse a regular reader, that the new reader is not high on Miller's priority list. Especially in issue #2, where Miller shows the story from the viewpoint of both Batman and Robin, a narrative device which robs the story of any mystery. We do not have an opportunity to wonder what Batman is doing, since he tells us. Ditto with Robin. I can only think Miller chose to tell the story this way because he realises most of readership are intimate with these characters. He judges the best use of the scene is to detail their innermost thoughts during their initial meeting. In terms of regular Batman readers, this may be the correct decision, but to the casual reader, this scene has emotional impact of a custard pie pushed in the face.

Then there's the extremely awkward question of Robin's age. In the regular DCU, is Robin really twelve at their initial meeting? Teenage sidekicks are an unwelcome hangover from the past, mercifully rare in Marvel (Rick Jones excepted, but he's grown up now). Fifty years ago, they were there to give the imagined reader someone to identify with. Now, in these less innocent (or less wilfully self-deceiving) times, you can't look at Batman hanging out with Robin and not think there's something very wrong about it. Could Miller have upped Robin's age to sixteen or so, or does this send the DCU into meltdown? As for Batman saying he's been keeping an eye on Robin, even before Robin's parents have been murdered, well, please make the nasty man stop, because he's scaring me.

This doesn't mean you can't tell good stories about Batman and Robin, of course. It's just best not to dwell on Bruce Wayne's motivations. Which is exactly what these two issues do.

So these issues are far from classics, but we should moderate our expectations as they are an origin story, and establishing the concept is often an unlovely task. And the issues do have their good points. They're straight forward, tell a story, and there's no wretched crossover rendering the whole endeavour incomprehensible. Unlike, says, JSA #77. Now that was what I would call a disappointing read.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home