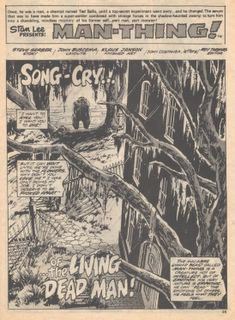

Song-cry of the living dead man

Man-Thing #12

So now I've gone and set myself a problem. I wrote a review of the first volume of Alan Moore's Swamp Thing, saying that I thought it was pretty good, but in some ways flawed. Greg, Marionette and Jim Roeg very politely responded that they thought I was wrong. Which is fair enough, because it wouldn't be much fun if we all thought the same way.

But then I got to thinking: what was my problem with Swamp Thing? The prose is beautiful, the plots well constructed, the ambience scary, the art fabulous. Why don't I love this book? And the answer is that I can't get over thinking it's derivative. It has such a resemblance to Steve Gerber's Man-Thing that I just can't view it as a great individual work. But it's been such a time since I read Man-Thing...

Man-Thing is one of those books which I read young enough in life that they shaped my perceptions of what comics (and, I think, literature in general) should be. I was about fifteen or sixteen, just graduating up from slug-it-out superheroes, and there was this disjointed, surreal strip quite unlike anything I had ever experienced. Now I don't want to get too drawn into this whole childhood comics Proustian memory thing, since Jim does that stuff so well, and, anyway, this is how my early years went:

But he did not finish his lessons. "Shirker. Slacker", they shouted. Oh childhood, the tedium of school.*

And who wants to remember that?

So to find out whether Swamp Thing is derivative or not, we can start by comparing Gerber with Moore, right? Well, yes. I know this is going to sound like I need a slapping, but I appear to have mislaid at least half my Man-Thing collection. When I was young, American comics were a rarity, and often a disappointment. Why? Because they usually had only one strip, and they were monthly or even (whisper it) bi-monthly. To someone brought up on the weekly schedule of British Marvels, monthly issues seemed unbearably slow (and this in the age before decompression). So, up until the early eighties, my comics were overwhelmingly black and white weekly reprints. And many were bulk buys of back issues, which I had no intention of treating properly. Once I gravitated to American comics, I revisited the early British ones at first only rarely, and then not at all. I moved house frequently, and my British comics stayed mouldering in their boxes. And somewhere along the way, half my bloody "Dracula Lives" and "Planet of the Apes" disappeared. A big pile of (amongst others) Marv Wolfman, Steve Gerber, Doug Moench, Gene Colan and Val Mayerik comics has simply vanished. Bollocks.

Man-Thing is a good candidate for being utterly disappointing on rereads. Firstly, it was from the early seventies, and much of the work before 1975 reads like a museum piece. Secondly, Man-Thing was extremely weird, and weirdness tends to age quite badly. So I'm relieved to say that I still like this story, and not for nostalgic reasons. I like it because it's good, and because of its startling originality.

The Man-Thing, an empathic creature who is drawn to strong emotions, comes to a former insane asylum deep in the swamp, where a man called Brian Lazarus has been sitting for days, attempting to write something. He is interrupted from his work by a man. Lazarus screams, and we see this scene:

The Man-Thing grabs one of the assailants, who evaporates in his hands. When he snatches Lazarus, his attackers disappear.

Lazarus explains that he was trying to write a work called the "Song Cry", finished it, and realised it wasn't good enough. It's become clear that Lazarus is on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Lazarus then meets Sybil Mills, a recently introduced cast member.

Lazarus: You know that old Beatles album? I put it on, and it just sounded like noise to me. Ugly, ugly, ugly noise. That's when I knew I was dying. But it wasn't just the music, it was everything. My whole life became one gigantic impenetrable wall of noise. My boss's yelling, the dog's whining, and the lies I had to write. All one big noise.

Gerber builds up the story around the "Song Cry", but there's a big problem coming. The depiction of Lazarus' instability with the assaults of his own subconscious is good. There isn't really a need for the reader to actually see the Song Cry, but unfortunately we do. It's a mish-mash of stream-of-consciousness surrealism, pretend song lyrics and prose poetry. I think I liked it more at fifteen than I do now; it sadly comes over as unstructured and pretentious:

Type dem words! Advertise? No, absurdize! Makes a man healthy, wealthy and how you despise dem golden slippers, mama, tucked in crawlspace unborn trauma. More!! More!! All this and more!! Our product has MORE of what you pay MORE for! A crumb in the loaf of industry, makin' life without identity, on the river island of eternity...

Well, you get the idea. You can see stuff like this in Bob Dylan's Tarantula, a truly unreadable book. Maybe it was a sixties thing.

Lazarus is now assaulted by his subconscious manifestations again, and the Man-Thing disposes of some of them. Then it realises that Lazarus is the cause of the emotional disturbances, and turns on him. Sybil intervenes to save him, and takes a punch in the face. Lazarus is shocked back to sanity by the selflessness of the intervention, and the manifestations vanish.

It's difficult not to think that this story is autobiographical. Lazarus is Gerber, and they have the same fears of bourgeois life. Lazarus is trying to write something, and failing, which makes you wonder if Gerber had a similar unrealised project. If attempting to write the "Song Cry" was Gerber's mistake, in a story about unrealisable writing it makes a certain kind of sense.

The ending, though: I can't see mental illness, any more than physical illness, being ended by a simple act of kindness. You wonder if Gerber, who has written on his website of his problems with depression, is searching for a resolution for issues which in the real world could never be solved in such an easy manner.

So I have reservations about this story, but let's be clear that its problems are those of over-ambition. Writers, especially young ones like Gerber was, have to get a few failures under their belt. I've got hundreds of punch-punch-punch superhero comics on my shelf, and I don't remember anything about them, but this one gets in your head and sticks there. Even if "Song Cry" doesn't totally succeed, the intent alone makes it an important book.

About influences

It's striking how many references Gerber in this story makes to the Beatles (a popular Scouse boy band), which might make them one of the conceptual ancestors of the Swamp Thing. Except their psychedelic era offerings seem to me to be confused rehashes of Bob Dylan's Bringing it all back home. It took me a long time to work out that Dylan wasn't being wholly original either, and that many of his ideas were reworkings of various poets such as WH Auden, Ezra Pound and especially TS Eliot, who Dylan namechecks in Desolation Row. Which puts The Waste Land, Eliot's towering masterpiece, as a major influence on all of them.

In fact, there are also a couple of hints of The Waste Land in Moore's work:

That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

This strongly suggests the scene in Swamp Thing #21 where the remains of the Swamp Thing starts to put out new growth.

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passes the stages of his age and youth

Entering the whirlpool.

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

I have Phlebas in mind when I think of the mariner in The Watchmen.

Eliot wasn't working in a vacuum, either. His Phlebas could have come from Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Or Shakespeare's The Tempest. And don't they all come from the grandfather of them all, Homer's Odyssey? And who knows what lost works Homer was building on?

Here's a challenge: how many comic books have been influenced by TS Eliot's The Waste Land? The first person to come up with five plausible examples gets a copy of Aleksandr Blok's Selected Poems. Who could resist a challenge like that?

*Boris Pasternak's description of Aleksandr Blok's childhood in Four fragments about Blok. Incidentally, if you haven't done so, you need to go and read Blok.